What investment activity, when done well, means better returns for investors, better run companies, better controlled societal and environmental footprints – all while being cost-effective?

It’s stewardship, where asset managers or asset owners engage and vote to positively influence assets they invest in.

Stewardship is expected by regulators to offset potential conflicts where there is separation of ownership and control. There are several examples of what can happen when there is too little oversight, among them accounting scandals, excessive executive remuneration, value destructive acquisitions, environmental damage and loss of customer trust.

Unfortunately, stewardship activities account for only a fraction of asset management industry activity. That’s because stewardship is tricky to measure and can involve uncomfortable conversations with company management. It is also difficult for asset managers to monetise given the free rider problem that stems from fragmented ownership interests.

In 2009, referring to the global financial crisis, the UK’s former Financial Secretary Lord Myners suggested institutional investors were “asleep at the wheel” when it came to stewardship. Perhaps it is now fair to say investors have one hand on the wheel, at least among some of the biggest asset managers and asset owners.

But there is still lots more to do.

Willis Towers Watson’s 2018 survey of the world’s largest 500 asset managers, conducted by the Thinking Ahead Institute, showed six managers (who collectively manage assets over US$17 trillion) grew total assets by 144 percent on average over the last 10 years, compared to 35 percent across the top 500. The managers are BlackRock, Legal & General Investment Management (LGIM), Northern Trust Asset Management, State Street Global Advisors (SSGA), UBS Asset Management and Vanguard.

Improving practice

“Passive management” is a misleading label when it comes to stewardship. More and more, index managers actively seek to improve the basket of securities within an index by acting as long-term owners.

All the managers in our sample acknowledge their responsibility and opportunity to create value in this area. They contribute to stewardship both at the company level and to various policy initiatives. All are signatories to numerous local stewardship codes.

The processes and areas of strength differ between managers which adds diversity – there is no single ‘right way’.

BlackRock: Voice from the top

BlackRock has a clear ‘tone from the top’ from Larry Fink’s well-known public annual letters to company CEOs. This has included a public commitment to double resourcing for the stewardship team which, at the time, was already the largest across the group of managers.

LGIM: Climate Impact Pledge

This is a well signposted multi-year campaign to encourage companies to manage their exposure to climate risk. Launched in 2016, LGIM issued a 2018 progress report naming leaders and laggards. While others note climate risk as a priority, the difference here is the level of coordinated effort and strong communication around a particular theme.

Northern Trust Asset Management: Hermes EOS

To augment its internal team Northern Trust Asset Management partners with Hermes EOS—a longstanding and high-quality third-party stewardship provider—to undertake company engagement in Europe, Middle East and Africa (EMEA). They have worked together on policy and other initiatives. This approach complements the internal engagement platform in the US. One solution to the ownership fragmentation challenge is for different asset owners and asset managers to pool resources and use a group such as Hermes EOS.

SSGA – Gender diversity on boards

Stewardship activity has in the past largely been kept behind closed doors. But if the objective is to achieve broad-based change then sometimes a creative public campaign is powerful. The Fearless Girl sculpture commissioned by SSGA in 2017 got people talking. SSGA identified over 1,200 companies across the United States, Australia, Canada, EMEA and Japan without a single woman on their board. They voted against the chair for over 500 companies each year—in 2017 and 2018—that failed to take adequate steps to address this issue. Partly in response to these efforts, 423 companies added a female director.

UBS – Solutions

UBS has created bespoke investment solutions which integrate stewardship, particularly in the areas of climate change and impact. These have been developed through leveraging partnerships with leading asset owners, academics, top universities as well as in-house intellectual capital.

Vanguard: Team construction

Vanguard’s team has been established and grown significantly over the last few years including new joiners with diverse functional experience from a variety of backgrounds. This helps them to engage credibly with directors on relevant topics (such as risk, audit, human capital, finance, legal, investments) to assess board strength and quality of process. Vanguard also appears to effectively leverage its relationship with certain active managers.

Where improvements can be made

There are several topics where progress seems slow and stewardship tools might be better applied (see the table below). While some may view this list as stretching, large indexation managers have a major opportunity and responsibility to bring robust stewardship with deeper engagement models – leveraging their long horizons, breadth of influence and sizable stakes.

| Board quality | Boards of corporate or non-corporate entities provide critical oversight. Each of the asset managers considers this area but we typically see limited emphasis on:

|

| Executive remuneration | An area that consistently takes up significant bandwidth and with strong shareholder rights, but evolution seems gradual. |

| Smaller companies | Tend to receive relatively limited attention, particularly companies based in markets away from the domestic base of the index managers (such as Asia). |

| Capital structure | Deterioration in corporate balance sheets, for example due to share buybacks is rarely discussed. Related, the challenge of balancing interests of bondholders and shareholders. |

| Climate risk | On everyone’s priority list but many progress initiatives lack sufficient urgency and depth. |

| Local market norms | Cultural nuances across markets can make pushing against the status quo challenging, however, areas such as limited gender diversity of boards in Asia or lack of auditor rotation in the US are often placed in the ‘too difficult box’. |

| Sensitive subjects | Areas where personal or political values meet financial value – remain underdone, for example transparency on corporate lobbying activities. Without full transparency it is difficult for shareholders to understand potential financial and reputational risks or determine if the board is adequately overseeing those risks. |

Resources

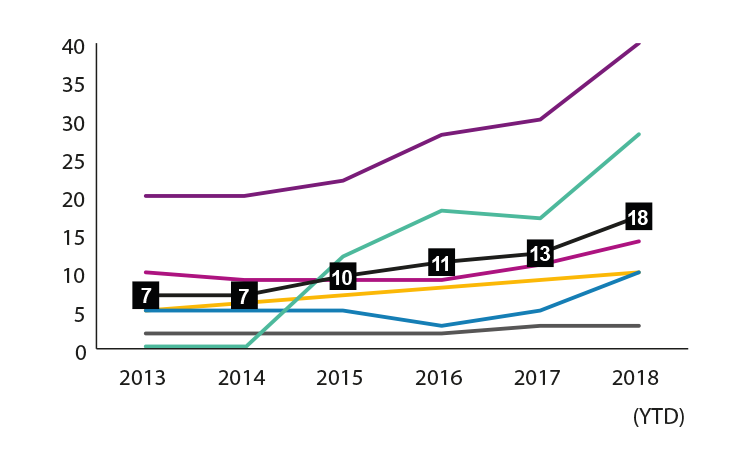

It is encouraging to see that the majority of firms have increased internal stewardship resources over time (see Figure 1). However, this u

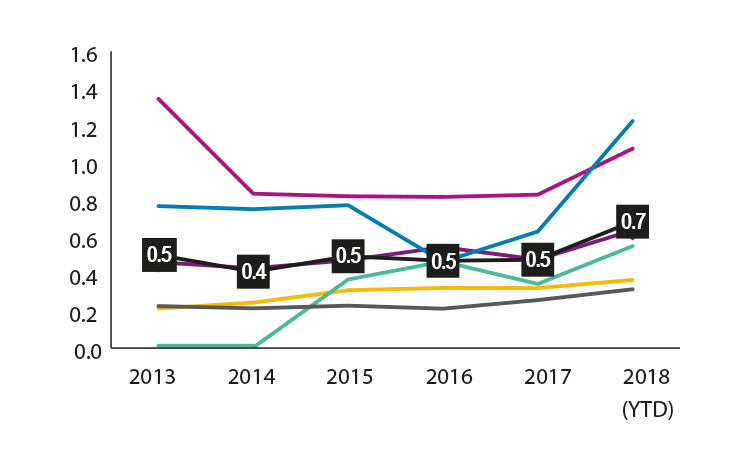

pward trend is less obvious when compared to total firm assets under management (see Figure 2) and compared to the total number of investment professionals employed.

Figure 1. Size of stewardship teams over time – the black line shows the average

Note: Figures supplied by managers; excludes wider firm resources that may contribute to stewardship activities such as internal active investment teams

Figure 2. Size of stewardship team per $100 billion assets under management – the black line shows the average

Note: For 2018 YTD, data is as at Q2 or Q3 depending on latest availability; assets data sourced from eVestment

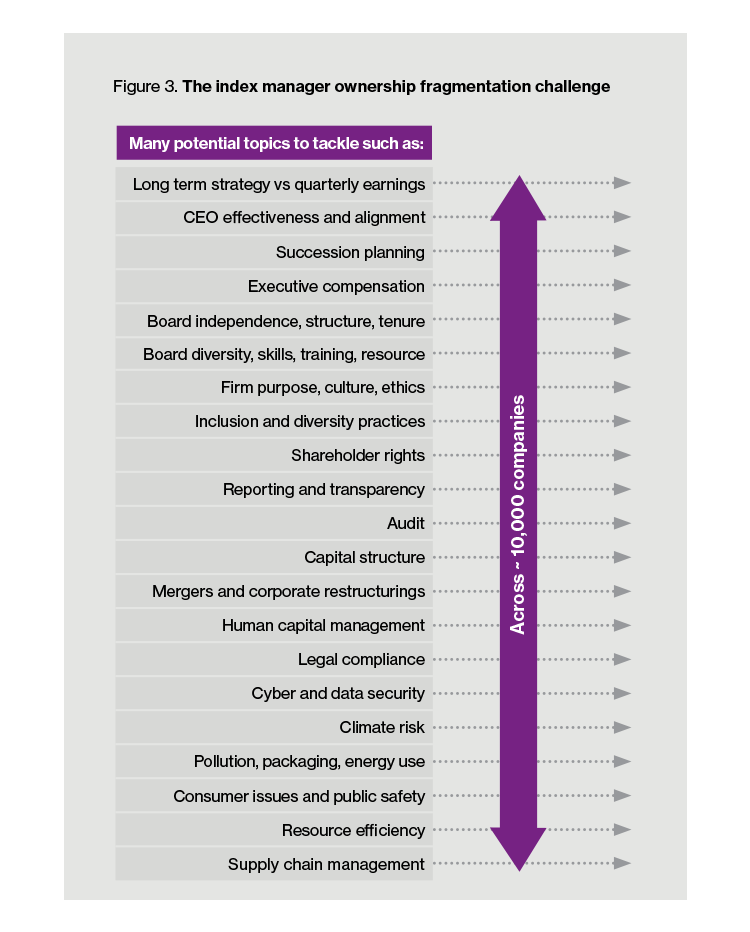

So what’s the right number? The indexation stewardship team job spec is vast given the spread of ownership interests (see Figure 3): corporate engagement on dozens of complex issues covering close to 10,000 companies, voting on tens of thousands of resolutions, regionally fragmented public policy engagement, research, disclosure and external communication. This practical task list alone necessitates far bigger teams and the value proposition further justifies increased resourcing.

If just a quarter of a basis point—often merely a rounding error—of assets under management was directed towards increasing internal stewardship resources, that could mean stewardship teams over ten times bigger than at present.

This would also allow hiring of people with more diverse and highly skilled backgrounds.

Clarity

There is a lack of tangible, specific milestones around what stewardship success looks like, even on prioritised topics such as remuneration, climate risk or board quality. Stewardship seems to lack urgency and accountability is soft.

This may lead to the pursuit and celebration of what are inadequate initiatives—in terms of timeliness, scope or magnitude—particularly in pressing areas such as climate risk.

Policies, high-level annual voting statistics and selected anecdotal examples of company discussions are useful but can paint an incomplete picture. Clearer objectives alongside detailed activity and impact reports on key stewardship themes would allow progress to be measured and enable more engaging communication with clients.

Another useful disclosure would be explanations of voting decisions, including related engagement activity, at controversial AGMs. Levels of transparency around stewardship activity currently differ widely by manager.

Voting

Care needs to be taken when reading into voting records. Sometimes an asset manager will be making significant engagement efforts behind the scenes with good progress on a particular issue such that a dissenting vote is then not required.

Still, at times there can be too much reticence to vote against company management in order to protect relationships and perhaps to avoid being associated with an ‘activist approach’.

Collaboration

There are pockets of excellent collaboration across the industry but inter-manager collaboration within our sample seems low. Large index managers are used to competing intensely for market share, but stewardship is an area where collaboration, not competition, is often in the interests of their clients.

Only the three smaller managers in our sample are signatories of Climate Action 100+, the world’s largest collaborative initiative around managing climate risk.

Leadership

The stewardship challenge calls for leadership-minded thinking and, particularly for large indexation managers, a universal owner mindset could capture both the responsibility and opportunity. They could more proactively set out their investment beliefs and consequently the standards expected of companies across a range of issues.

For asset managers to put both hands firmly on the wheel, more of their clients and intermediaries need to pay close attention and call for a safe journey. Then there’s reason to be optimistic about the future of stewardship and the benefits across the entire value chain.