The good news for Australians is they may not spend as much in retirement as they expect. The bad news, however, is retirees are uncertain of what they actually can afford and if they have enough savings or not, leading them to being frugal for fear of running out of money.

Mercer recently surveyed 1000 Australians aged 55 and older, with at least $50,000 in their super accounts, how long they thought they would live, how much money they expected to spend in retirement and what their concerns were about aged care costs.

The first in a three-part series called Great Expectations: Attitudes and Behaviours amongst Australian Retirees Part 1: Spending Preferences, shows where pre- and post-retirees expect to get their income once they retire, how much they expect to spend and whether this aligns to current retiree experiences.

Co-author Will Burkitt, Mercer Australia’s post-retirement innovation leader, says expectations differ greatly from reality.

While the survey found most retirees (81 per cent) will source their retirement income from either superannuation or the Age Pension, many are spending significantly less in retirement than they expected.

Retirees spending less than they expected

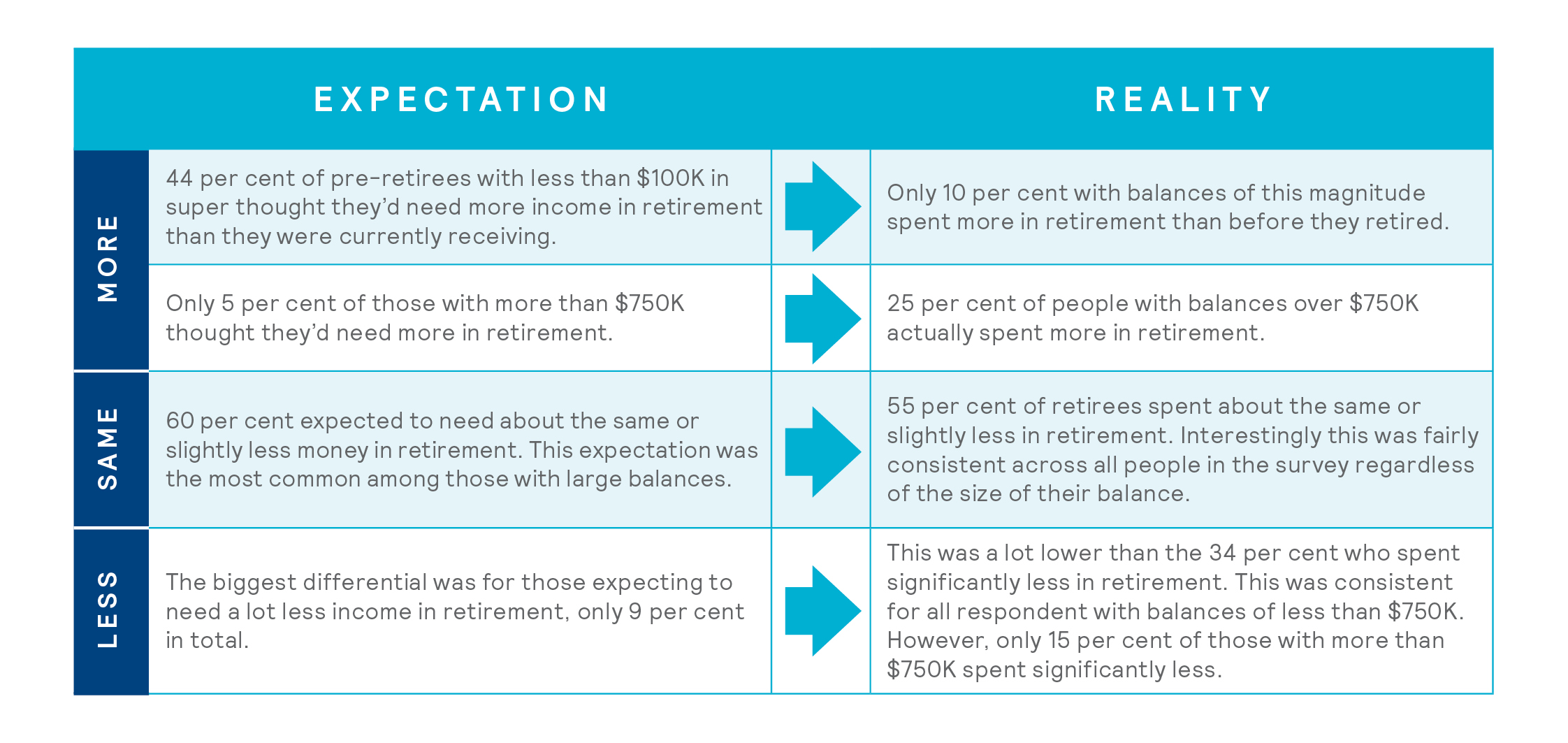

Mercer found 44 per cent of people surveyed, with less than $100,000 in their super accounts, thought they would need more income at retirement than they were currently receiving but the reality was only 10 per cent of people with these balances, spent more in retirement.

“The amount of money people think they will need in retirement does not align to what retired people are actually spending. If we assume this is because people do not have the savings they need and are forced to spend less in retirement, it demonstrates a clear need for better communication and engagement,” Mr Burkitt says.

“For example, super members’ annual statements have historically only included their balance but this is very difficult to convert into an income. You can see how someone with $100,000 in their super could think this will be enough because it’s a lot of money. However, in reality, this balance is only likely to achieve $4400 a year.”

He says many Australians reaching pension access age today will spend 20 years or more in retirement which puts significant pressure on their personal retirement savings and future Government budgets from expenditure on the Aged Pension, aged care and health support.

“From a pure economics perspective, every dollar saved now needs to work harder to maintain our standard of living,’’ he says.

Australians underestimate how long they will live

In line with similar research, Mercer found young people are underestimating their life expectancy, currently at 80.5 years for men born in 2017 and 84.6 years for women, yet older people are the opposite by overestimating their life expectancy.

In reality, the Mercer report shows for Australian retirees on a traditional account-based pension, this could mean initially withdrawing too much, depleting balance levels and then psychologically wrestling with the concern in later life of living longer, than average life expectancy, however without the necessary savings to support them.

“Most people don’t have an accurate enough understanding of their future life expectancy and needs. There are two gaps for Australian retirees currently; firstly, there remains a lack of cohesive information provided to them, in a format which is easy to access and understand. Secondly, not enough Australians proactively create a retirement plan,” Burkitt says.

“Australians leading into retirement are underestimating how long they’re going to live, which may lead them to spend too much or misalign their expenditure in the earlier years of retirement. Only to then become concerned about not having enough savings left, particularly for unforeseen health or aged care costs which can lead to people underspending in the middle and later years of their retirement. This is exacerbated by their developing concern about the possibility of living longer than they initially expected. This is depriving Australians of living a quality of life which maximises their potential throughout retirement,” Burkitt says.

“It also speaks to those potential gaps that people fear around large amounts for aged care and other unknowns.’’

Burkitt says longevity products, such as annuities, are popular in other countries, and can ensure an income for the whole of life, but Australians have seen “a few false starts”.

“The longevity product market is really at its infancy and has had a couple of false starts previously … the problems include the complexity of these products for people to understand, inadequate product structuring, concerns of foregoing hard-earned savings now for a potential future benefit and locking in low-income distributions because of the low return environment that we’re in,’’ he says.

“The prolonged low-interest rate environment has favoured home-owners with debt during their accumulation working phase but the opposite for Australians’ in their retirement who no longer work to receive income and instead rely on investment returns to preserve their savings levels whilst drawing on them for day to day consumption needs.’’

Annuities are products acquired at the start of retirement which can quarantine a recommended 20 to 30 per cent of balances to deliver long term income distributions.

“If you have say $500,000 at retirement, this could mean putting away one to two hundred thousand dollars into a product which has the benefit of providing comfort that you have a certainty of receiving income to use in your later years, rather than running out,’’ he said.

Burkitt says Mercer’s report was designed to tap into a normal Australian perspective on retirement and to understand retiree behaviour and expectations.

Mercer’s sequel report, Part 2: The Ideal Retirement Solution, explores desired retirement income solution features and how these might impact on Australian retiree behaviour. The final report in the three part series will look at retiree awareness of existing options as well as views on financial advice.

It comes as former Liberal treasurer Peter Costello said Australia’s $2.7 trillion superannuation system has focused for too long on the accumulation phase without planning for how Australians will spend it in retirement.

“The Government concentrated on getting money into superannuation but didn’t show much interest in what happened to it,’’ he told ABC’s 7.30 program recently.

Low concern about aged care costs – a blindspot

Stories emerging from the current Royal Commission into Aged Care are likely promoting Australians’ awareness of the need for quality ageing care and living, but most early retirees are not immediately concerned with the costs, and of finding it, Mercer says.

Almost half (49 per cent) of pre-retiree men were not concerned about aged care costs, suggesting this issue was not at the forefront of people’s minds even as they age, Burkitt says.

“The main difference we saw was between men and women with 35 per cent of women saying they were concerned compared to just 18 per cent of men,’’ he says.

“That’s not surprising. Women live longer than men on average and secondly, women are more likely to be the primary carer within the family. Carers Australia found that 70 per cent of primary carers are women.’’

“I’m concerned that not enough people understand ageing care and living needs for themselves, or in many cases for their parents; this

forces them into the horrible situation of reactively finding care for home or moving to a residential aged care home whilst under emotional duress, taking large amounts of time to navigate the complexities of the aged care system and having to make one of the most important and financially large decisions of their lives,’’ Burkitt says.

“Most people prefer not to talk with friends and family about ageing and the connotation of deterioration in life leading to death.

“Fear drives people not to address it and that is the worst thing someone, and a family, can do.

“It may be they already have plans in place for ageing care and living arrangements or perhaps, more likely, there is a lack of understanding of the cost, time and emotion involved.”

Burkitt says super funds are one of the most trusted institutions within an Australian’s life and hence they are in an enviable position to help members navigate the complex issue of aged care by educating retirees and directing them towards suitable solutions.

While funds are finding ways to engage with members as early as possible, the optimal time seems to be around the age of 50, when members have almost paid off their mortgage, school fees are coming to a close and they begin to focus on planning for retirement, Burkitt says.

While funds are finding ways to engage with members as early as possible, the optimal time seems to be around the age of 50

Mercer is in discussions with some of Australia’s largest superannuation funds on helping them design fit-for-purpose solutions for their members and customers based on the report’s findings.

“Super funds have a unique opportunity to extend the strong foundation developed over the past 27 years since compulsory super was introduced to now serve their members in a much more holistic and integrated manner as they enter into and within their retirement. Serve them for their real-life retirement needs across wealth, health and career,” Burkitt concludes.