Sponsored content by Aviva Investors

In February 2021, Aviva Investors announced its climate engagement escalation programme, focused on 30 of the most systemically important carbon emitters in the oil and gas, metals and mining, and utilities sectors. Aviva Investors clearly stated that if companies fail to meet its expectations over the next three years, it will divest across both its equity and credit portfolio.

Tough action like this is needed, as preparing for a world focused on a “net zero” goal will be one of the hardest tasks faced by the human race. The number of countries and companies supporting the move to a lower-carbon world is growing, but as we outline in this article there are many practical challenges remaining as we chart a path to net zero.

1. Decarbonisation: An epic challenge

Lockdowns brought an unprecedented slump in global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions. The cleaner air and a resurgence of wildlife revealed a different world, as workplaces closed, travel was reduced, and people stayed at home.

“The immediate impact of COVID-19 was a seven to eight per cent reduction in CO2 emissions versus 2019,” says Richard Howard, research director at the energy analytics group, Aurora Energy Research. “The challenge now is how we reboot the economy and move forward. We need to reduce emissions by around that amount each year from now on for decades if we are to stay on a trajectory to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees [the goal of the 2015 Paris Climate Agreement].”

It means weaning society off fossil fuels as well as certain chemicals and plastics.

“(Climate change) mitigation is as much about stopping the damage to key parts of the natural environment which inhibit the take-up of carbon, and enhancing that take-up through policies to increase trees, grasslands, the take-up of carbon in the soils, and the protection and enhancement of peat bogs,” notes Dieter Helm, professor of energy and economics at the University of Oxford.

Ultimately, achieving net zero may also need industrial solutions, sucking CO2 from the air (direct air capture) or compressing it and storing it underground (carbon capture and storage).

2. The climate progress report: Disappointing

A quick glance at progress from co-ordinated climate action is not encouraging. Aside from the reductions associated with the global financial crisis and COVID-19 lockdowns, the trajectory for global emissions has been up. And there is already enough carbon-fuelled plants in place to propel the world over the damage-limiting target agreed in 2015.

But extreme climate events have focused minds and calls to build back better have intensified. Initially, only Europe was heavily invested politically in emissions reduction, but momentum is accelerating elsewhere. Canada, South Korea, Mexico, Chile, Japan, South Korea and South Africa are all part of the growing club taking steps to legislate for net zero. China has joined too, albeit with a 2060 target; a “giant step” in the fight against climate change, according to the Energy Transitions Commission.

Now the US is also back in the room, with Joe Biden pledging to pour up to $2 trillion of federal funds into climate action.

3. Directing finance flows towards net zero

Concerted effort is needed to meet the ambition set out in the Paris Agreement – to make financial flows consistent with climate action goals. “Globally, around $300 trillion of investment is going to be required over the next thirty years – that’s like rebuilding the US entirely, from the bottom up, every two years for the next three decades,” says James Belmont, climate risk lead at UK management consultancy, Baringa.

Nevertheless, the nature of climate risk makes assessing how the land lies particularly difficult for commercial financiers. “We cannot expect to keep plodding along in some kind of equilibrium,” Belmont adds. “We are either going to have a lot of transition or a lot of physical change; we are probably going to have some messy combination of the two. This is not a stress test away from a central case, in the way financial services firms normally conceptualise it.”

4. Policy priorities: Seeking direction

Policy is the hard part, because each country contemplating a net zero pathway faces its own unique challenges. The solution can never be one size fits all.

The most commonly cited action economists and analysts believe will speed the journey is the introduction of coherent carbon taxes, to ensure polluters pay. Without them, consumers fail to realise the environmental costs of their actions, and prospects for technologies that might aid the transition are dampened.

5. The rise of renewables

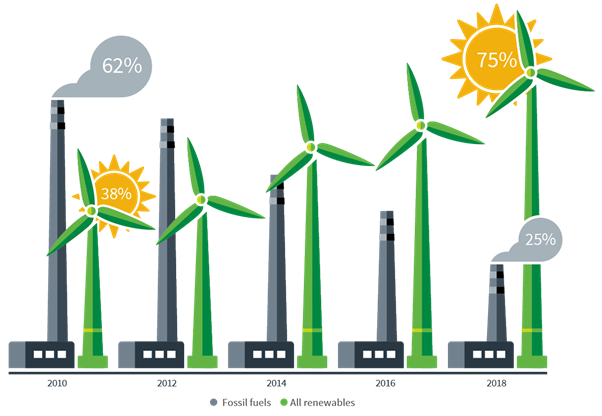

Meanwhile, the shift towards renewables has been a resounding success (see Figure 2), which could have important spin-offs.

Figure 2: Power to renewables: Net global power capacity additions

All Renewables: Includes solar, wind, geothermal, biomass and hydro, and excludes energy storage technologies. Source: BloombergNEF, October 2020

With ample renewables, plentiful energy can be generated from hot sunshine or gusty weather when energy demand is low. In future, this could be put to work to produce hydrogen via electrolysis, (‘green hydrogen’, if the underlying energy source is 100 per cent renewable), keeping installed capacity at work.

In this scenario, hydrogen is not just a fuel that could be used to power transport, but also an important renewable energy store.

“It is possible to envisage a situation where a certain amount of installed capacity combined with specific weather conditions could send the electricity price close to zero,” says Howard. “Imagine that is the point when all the electric vehicles switch to charge, hydrogen electrolysers switch on and other demand kicks in. If electricity becomes extremely low cost at times, we might start doing things differently.”

6. Dampening appetite for carbon

In setting the course for net zero, the management of the built environment is a critical consideration. “COVID-19 has triggered a real estate crisis, and that has sharpened minds,” says Sam Carson, director of sustainability at Carbon Intelligence, a consultancy advising companies on how to reduce their carbon footprint.

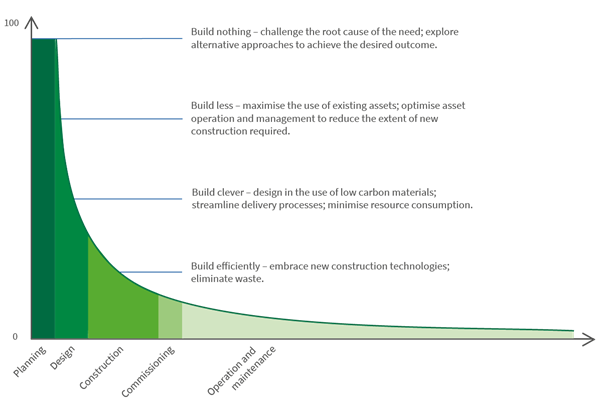

For an asset owner, not carrying out major construction works has the greatest positive carbon impact (see Figure 3), but ‘building less’ and ‘building clever’ with lower carbon materials can be advantageous too.

Figure 3: Carbon reduction potential

Source: HM Treasury, Infrastructure Carbon Review 2013

“Those managing the built environment have generally not had constraints on the quantum of space they can build,” Ed Dixon, head of ESG for real assets at Aviva Investors points out. “A skyscraper might be knocked down and replaced, although it could be refurbished. There is nothing in current policy or regulation to prevent that. But society simply cannot afford this type of growth. The solution must be making better use of the assets we already have.”

These considerations are receiving greater attention with the arrival of carbon accounting. In future, the price of carbon is expected to be significantly higher; commercial property developers are unlikely to pay for carbon-heavy materials if they will not generate significant value in return.

“That is what will shift the market,” says Carson, adding that those failing to address carb

on issues swiftly are likely to see the value of their assets fall.

7. Being mindful of net zero gains

The tone of the net zero debate often feels heavy, weighted towards industry, the asset mix in the power sector and the like. But even with the best will in the world, net zero will not be achieved without careful consideration of how to be better custodians.

“Meeting net zero implies a level of awareness and collectivism that we struggle to have as a society now,” Belmont admits. “But we are witnessing some important changes. It feels like a tipping point.”

“As professionals, we tend to talk in terms of various scenarios, and we compare the risks and costs,” says Oliver Rix, partner for energy, utilities and resources at Baringa. “But we also need to talk about what it means for people. It’s about better air quality, less noise pollution, using land more sustainably, having a well-managed countryside and improving biodiversity. Transport will be revolutionised too. These are huge advantages; we need to keep them in mind.”