“All the world’s a stage, And all the men and women merely players.” (Shakespeare, As You Like It. Act 2, Scene 7). The gender pay gap is an economic representation of a woman’s position in the economy compared to men. Despite the extensive reporting mandates that are in place in Australia, our pay gap (14.1 per cent) remains above the OECD average (11.6 per cent).

The gender pay gap is an internationally established measure of the difference between the average weekly full-time earnings of women and men in the workforce, expressed as a percentage of men’s earnings. It is not a comparison of like-for-like roles.

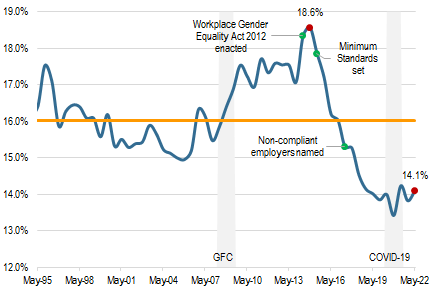

The pay gap in Australia has been steadily compressing over the years, in particular since peaking at 18.6 per cent in Nov-14. Progress was notably impaired by the Global Financial Crisis, which saw the pay gap rise 100bp between November2007 and November 2008. The Workplace Gender Equality Act was passed in 2012 and, combined with the introduction of industry-specific minimum standards in 2015, the pay gap began to narrow. As at May 22, the pay gap sits at 14.1 per cent.

Australia is one of few countries that mandate the reporting of gender-related data and the ASX Corporate Governance Council has placed increasing focus on gender diversity in their recommendations. Despite this, other global countries outperform. Spain, the UK and Italy recently passed legislation requiring the reporting of pay gap information and have a lower pay gap versus Australia. Spain also requires companies to show clear action plans and progress towards addressing pay discrepancies.

Economic drivers of the pay gap

One driver of the pay gap is that women tend to make up the greatest proportion of workers within lower paid industries, such as Healthcare. Conversely, men make up the larger share of employees within Mining; the highest paying industry in terms of weekly average earnings. Highly segregated industries make it difficult for women to access jobs in better-paid industries.

Another factor that contributes to the gender pay gap is the underrepresentation of women in senior and leadership roles. Nearly 60 per cent of managers in private companies are male and over 80 per cent of CEOs are male.

As a result, men make up 75 per cent of those that earn more than $2,500 a week and only 34 per cent of those that earn less than $500 a week.

The largest contributor to the gender pay gap is the proportion of time women spend out of the workforce to take on care responsibilities and household work.

In Australia women spend 64 per cent of their average weekly working time on unpaid domestic work and childcare, compared to 36 per cent for men. The participation rate for parents with a young child (age 0-5) is much lower for mothers than fathers and nearly 60 per cent of women with a young child work part-time, compared to only 7.9 per cent of fathers.

Research on the “motherhood penalty” is at an early stage. In July 2022, economists from the Treasury conducted the first analysis in Australia on the impact of motherhood on a woman’s lifetime earnings. The report found a “significant and persistent penalty attached to having a child for women, but not for men”.

Company policies that support flexibility for parents and carers are important in encouraging female participation in the workforce and help to narrow the pay gap. Imbalanced parental leave schemes continue to place most of the care upon women. The rate of parental leave take-up from men in Australia is low compared to other global countries and 99.5 per cent of primary carers’ leave is taken by mothers.

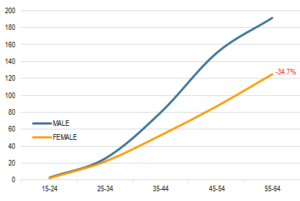

This pay discrepancy compounds over time, resulting in women retiring with 35 per cent less in superannuation than men. Super balances start to diverge between the ages of 25 and 34.

Policies that support pay equity drive returns

The increased scrutiny of the listed market has driven greater action on diversity. Nearly 90 per cent of listed companies offer primary carer leave versus 54 per cent of all private companies in Australia. Our analysis found that the top 20 companies in terms of gender equitable policies tend to have higher return on equity.

Importantly, 85 per cent of ASX-listed companies offer breastfeeding facilities to new mothers. Only 6 per cent of ASX companies provide on-site childcare and 8 per cent offer employer subsidised childcare. A number of listed companies also voluntarily publish their own gender pay gaps. Westpac Banking Corp (WBC) and Commonwealth Bank (CBA) announced in April this year that they will no longer prevent employees from discussing salary as part of their initiatives to help narrow the gender pay gap.

While the disclosure of gender pay data is mandatory in Australia, it is not made public. That is set to change following the Jobs and Skills summit last week, where the Albanese government agreed to legislate the public disclosure of companies’ gender pay gap data to the Workplace Gender Equality Agency. Such reporting requirements have notable impacts on the pay gap. In 2017, when the UK Government mandated the public reporting of pay data, the gender pay gap fell by approximately 1.1 per cent in the four years to 2021. Public reporting is an important step in helping to narrow the gender pay gap in Australia, encouraging employers to evaluate their own workforces and pay gaps and be transparent in their actions to narrow it.

For access to the full report, please contact Emily on emily.c.macpherson@jpmorgan.com.