Ageing populations continue to pose a challenge to governments worldwide, with policymakers struggling to balance the twin goals of delivering financial security for their retirees that is both adequate for the individual and sustainable for the economy.

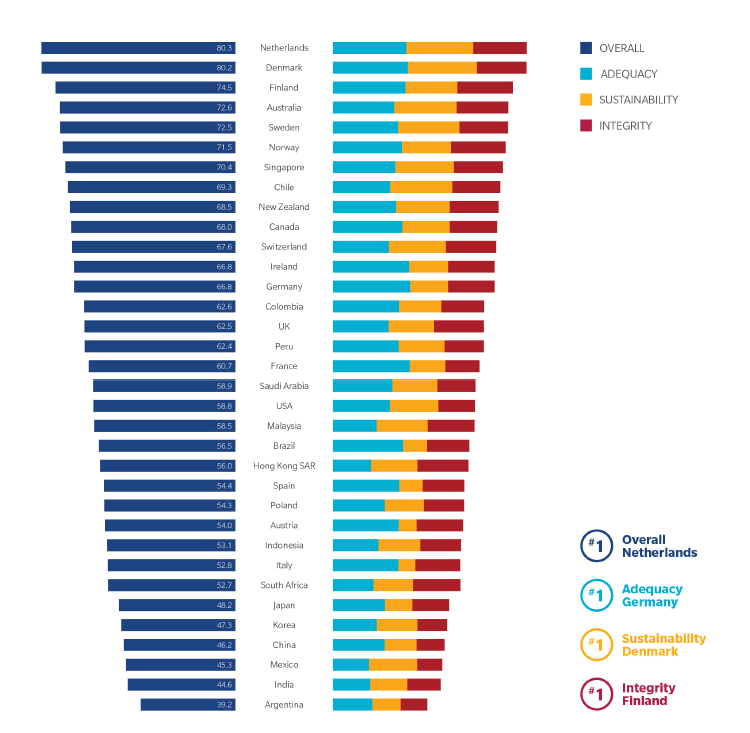

Now in its tenth year and measuring 34 global pension systems, the Melbourne Mercer Global Pension Index reveals who is the most and who is the least prepared to meet this challenge.

This year the Index reveals that many North-Western European countries lead the world in providing the best pension systems for their citizens. The Netherlands, with an overall score of 80.3, just beat Denmark to first place by 0.1, a spot held by Denmark for six years. Finland bumped Australia (72.6) out of third place with an overall score of 74.5 and Sweden (72.5) came in fifth place.

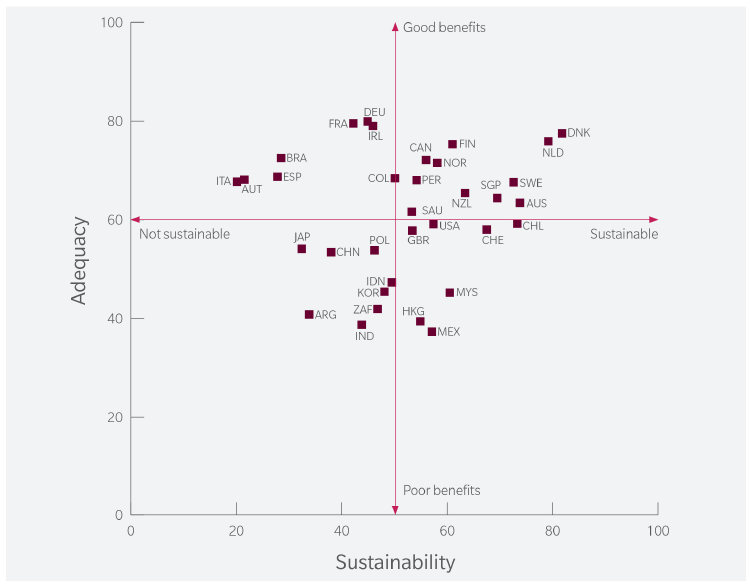

Common across all results was the growing tension between adequacy and sustainability. This was particularly evident when examining Europe’s results. Denmark, Netherlands and Sweden score A or B grades for both adequacy and sustainability, whereas Austria, Italy and Spain score a B grade for adequacy but an E grade for sustainability that visibly points to areas requiring reform.

Author of the report and senior partner at Mercer, Dr David Knox explains: “The natural starting place to having a world class pension system is ensuring the right balance between adequacy and sustainability. This year we see that some countries are doing reasonably well in both adequacy and sustainability, but there are others where the benefits for many retirees may be adequate, but they are unlikely to be sustainable – Austria, Italy and Spain are examples and you’d probably mention Brazil and Japan in there as well.”

What the report highlights is that countries are in different positions in terms of the long term relationship between adequacy and long-term sustainability.

“It’s a challenge that policymakers are grappling with,” says Dr Knox. “For example a system providing very generous benefits in the short-term is unlikely to be sustainable, whereas a system that is sustainable over many years could be providing very modest benefits. The question is – what’s an appropriate trade-off?”

As highlighted in Chart 1 below, all systems should aim to adjust their settings so they are moving towards the top right quadrant. By looking at the common features of those in this space it becomes easier for others to design and adapt their own systems. From an Australian perspective, adequacy and not sustainability is the main concern.

From an Australian perspective, adequacy and not sustainability is the main concern.

Chart 1: Adequacy versus Sustainability ratings for global pensions systems

Coverage becomes more important

Dr Knox adds that beyond the challenge of balancing adequacy and sustainability, an emerging dimension to the debate about what constitutes a world class system is “coverage” and the proportion of the adult population participating in the system.

“In some countries, broad coverage has been successfully accomplished through compulsory workplace pension systems or, in some cases, auto-enrolment arrangements,” he says.

“However, with changes in the way people are working around the world, we need to ensure these schemes include everyone so that the whole workforce is saving for the future. This includes contractors, self-employed, and anyone on any income support, be that parental leave, disability income or unemployed benefits.”

Introducing a new question to the index: Household debt

An important adjustment to the adequacy sub-index this year was a new question relating to household debt to gain a more holistic view of retirement adequacy.

The index has always considered the level of household saving as it represents an important contribution to the level of non-pension saving. However, this current question relates primarily to the flow of household savings and does not consider the accumulated level of household debt. In some countries where there is significant household debt, such as Switzerland and Australia, some retirees will use superannuation savings to pay off their debt, resulting in retirement savings being reduced and benefits being lowered.

“What we try to do is go beyond the three pillar approach and consider five pillars thereby considering what happens outside the pension system. That’s where the household debt comes into play,” Knox said. “When we’re talking about retirement pensions, we need to make sure that we don’t just look at super, and we don’t just look at the aged pension, and voluntary savings, but we need to look at household savings, home ownership to get the full picture.”

Examining five pillars—including household savings and household debt—allows a fuller picture that can assist in designing regulation and taxation policy to encourage complementary behaviour rather than perverse behaviour, Knox said.

So why did Australia slip from third to fourth in 2018?

David Knox says that Australia’s downgrade is primarily due to a toughening of the assets test and the inclusion of the level of household debt (as noted above) as part of the adequacy sub-index.

“The OECD produces the net replacement rates every two years for their member countries and we have used these results for this year’s study and it’s caused a significant reduction in our net replacement rate,” Knox said. “The cause is very simple. Although people are saving through super during their career, the stronger assets test means they are getting reductions to their Age Pension. Their net income is lower in retirement, so that’s the primary reason for the lower score.

“What it does highlight, and it’s highlighted in other systems as well, is that policymakers need to make sure that the various pillars work together, and that these pillars provide the right incentives for people to save for the future.”

2018 Results

What does the future look like?

Some pension systems face a steeper path to long term sustainability than others, and all start from a different origin with their own unique factors at play. Nevertheless, every country can take action and move towards a better system. In the long-term, there is no perfect pension system, but the principles of best practice are clear and nations should create policy and economic conditions that make the required changes possible.

This year’s Index now includes Hong Kong SAR, Peru, Saudi Arabia and Spain, covering 34 systems against more than 40 indicators across adequacy, sustainability and integrity. This comprehensive approach highlights an important purpose of the Index – to enable comparisons of different systems around the world with a range of design features operating within different contexts and cultures.

The only commonality globally is that no-one is satisfied with their own country’s pension system, Knox added.

“We see this in Australia, with the Productivity Commission report, and yet we’re still coming 4th out of 34 systems,” he said. “We see in the Netherlands where there’s a lot of concern, a lack of trust in the system, yet they came out as the leader this year. One thing this report can show is that no system is perfect – there will always be shortcomings, there will always be room for improvement, but if you’re in the top half-dozen systems you’re doing some things well, and don’t discount that.”