My 68-year-old father says he can’t see himself being 70 years old. Why then are we surprised when a 30-year-old can’t imagine growing old?

Our ability to imagine future possible scenarios, or perform ‘mental time travel’, is not only fundamental to who we are, it’s been shown to directly relate to our propensity to save for the future.

Specifically, it’s been found that the more connected we currently feel with our idea of ourselves in the future, the more money we are prepared to forego in the present and put aside for the future.

The future self as a stranger

“Why would you save money for your future self when, to your brain, it feels like you’re just handing away your money to a complete stranger?” said UCLA psychologist and researcher Hal Hershfield.

The degree that we “connect” with our future selves has been measured by a team of psychologists at Stanford University and UCLA Anderson School of Management using neuroimaging. The results are startling. They indicate that the person we think of in the distant future (that is, our “future self”) has more in common with a stranger than it does with our current selves.

This finding, connected to the principle of “present-bias” (or the tendency to give stronger weight to payoffs that are closer to the present time), has implications for many aspects of our lives, not least, our motivation to save.

Future self connection translates to long-term savings

Something as simple as imagining or writing to oneself at a date in the future has been shown to positively impact people’s connection with their future selves (you can try this out at futureme.org).

To test the effect of the ‘future self’ connection on savings behaviour, Hershfield and his colleagues ran a series of tests from 2009 onwards.

To overcome any difficulties participants might have in imagining their future selves, Hershfield and his team created virtual simulations of participants’ retirement-age “future self”, projected 40 years into the future.

The results?

The individuals who interacted with the virtual simulations of their future selves were willing to allocate twice as much to their retirement account compared with their counterparts who did not see their simulated future faces.

An alternative study by Hershfield found that people’s real-life financial positions are indicative of how connected they feel to their hypothetical future “self” in ten years’ time.

The correlation was that the better your current overall financial position is, the more connected you are with your ‘future self’.

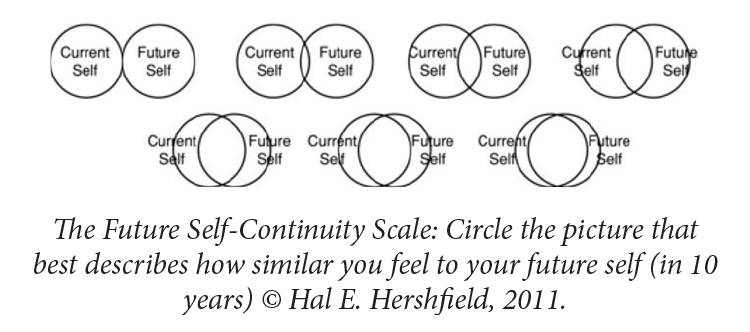

These findings were obtained by asking a selection of individuals aged 20-86, to indicate their personal sense of future self-continuity, using Hershfield’s purpose-built scale (below). The same individuals were asked to give a dollar value of their overall financial position.

The results revealed a direct correlation (controlled for age) between the participants’ future self-continuity score with their real-life overall financial position. This is significant, as it suggests that finding ways to help individuals better visualise and feel connected to how they could be in the future, could dramatically improve their savings rates.

Ways to harness the ‘future self’

Bank of America’s Merrill Edge launched a “Face Retirement” campaign in 2012, which put these findings into action. It resulted in nearly 750,000 people increasing their savings rate for their retirement and a campaign that went viral.

To achieve these results, Merrill Edge provided a face-ageing app for customers, accompanied by the message: “if you could see yourself in retirement, if you could age your photo and come face to face with the future you, it just might change how you think about the future. And how you prepare for it.” Customers used the app to view themselves virtually ageing – wrinkles and all – in 3D. While the campaign is no longer live, there are several virtual ageing tools available, such as the “AgingBooth” app or the ageing filter on Snapchat if you’d like to try it for yourself.

Another campaign by Aviva in the UK, demonstrated the emotional reactions and surprise people experience when their future lives turn out differently to how they’d anticipated. The “Reality Check – Shape My Future” campaign was launched in 2016 and is still live.

The campaign featured two individuals with contrasting levels of savings, who were placed in their simulated future lives for a week and filmed – being fitted with prosthetics to age their appearance and living on the amount they were projected to have saved in retirement. While the results of the campaign are not publicly available, the longevity of the campaign coupled with the impact the experiment had on the individuals themselves is noteworthy.

Behavioural economists Richard Thaler (Nobel Laureate, 2017) and Shlomo Benartzi famously boosted average savings rates more than 350 percent with the Save More Tomorrow™ (SMarT) program they designed for Allianz – originally trialled in 1999 (and still running).

Of the 78 percent of participants who joined the program, which had members commit in advance to allocating a portion of their future salary increases toward their retirement savings, 98 per cent remained through two pay rises in the program’s first three and a half years. Thaler and his work have been credited with saving Americans over $30 billion in retirement savings over the past decade.

Prudential Financial have also tapped into findings from behavioural science, partnering with Harvard Psychologist Dan Gilbert to create crowd-sourced campaign “Bring Your Challenges”, launched in 2011. Prudential performed a series of activations through its “Challenge Lab”, challenging and educating customers to think more realistically about their retirement.

Last year, in partnership with the Young Entrepreneur Council at South by Southwest® (SXSW), Prudential brought its latest white paper, “The 80-Year-Old Millennial”, to life. They co-hosted a networking lounge and futurist panel discussion aimed at helping millennials visualise what work, technology, health and money will look like in the decades to come. The panel event included a digital aptitude test so that attendees could determine their persona (such as Futurist, Trailblazer, Technocrat) which generated a 3D-printed object representing their persona (the test is available at 80yearoldmillennial.pru).

“In order for people to impact their future, they need to envision it first,” says Niharika Shah, Prudential’s VP and Head of Brand Marketing and Global Insights. “Research has shown us that we all—not just millennials—have difficulty seeing more than ten years in the future. Creating an experience enabled us to spark that thought in the minds of millennials in a much more impactful way than simply handing them the results of our study. And what better place to do this than at one of the most well-known interactive media festivals?”

What does this mean for superannuation?

Behavioural Scientist Johann Ponnampalam (PhD), affirms, “the battle with the future self is one of the fundamental challenges of financial preparedness and wellbeing.”

With this in mind, how can super funds help members better connect with—and act in—the best interests of their long-term future selves?

The answer could be as bold as Prudential’s SXSW event or extend beyond current horizons, encapsulating more of the

senses with technologies such as voice ageing and more immersive forms of Virtual Reality with more realistic scenarios.

Or perhaps we look to Damon Gameau’s recent impact documentary film 2040, which paints a vivid vision of how the world could be in 20 years, blending a mix of traditional documentary with dramatised sequences and imaginative visual effects to share his ideas with the world (see whatsyour2040.com).

It could involve the more subtle, everyday ways that we interact with members – whether it be through member services call teams, our websites, seminars or our online or physical forms.

After all, as Ponnampalam suggests: “Every interaction matters, therefore every interaction can be behaviourally optimised.”

At the very least, it’s worth remembering that for some members, their future selves are nearly as much of a stranger to them as they are to you.

While the answers may not be immediately obvious, this does not mean we should shy away from the question. Every individual working in super, whether they know it or not, can be an advocate for the future self and more broadly, an agent for behaviour change.

Let’s get creative.