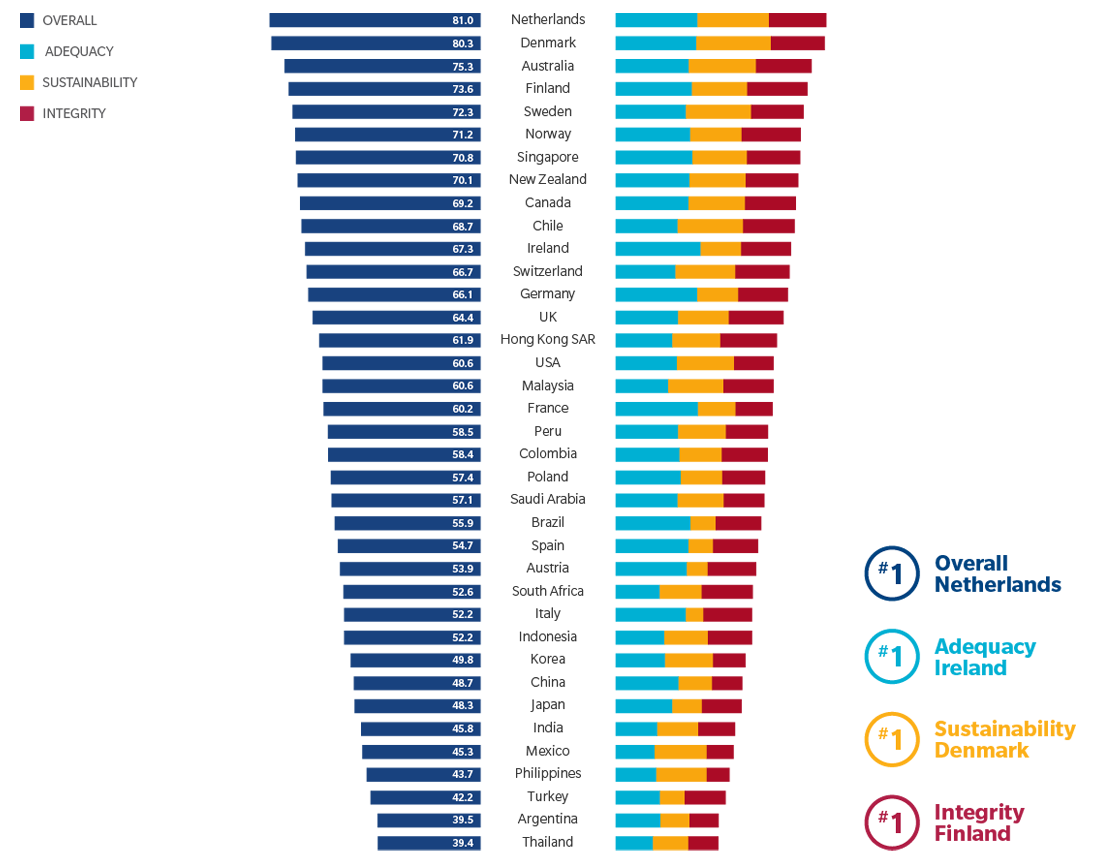

Australia’s retirement savings system continues to score well globally on metrics assessing the adequacy, sustainability and integrity of the system, with the Netherlands and Denmark scoring first and second and Australia third place. The Index compares 37 retirement income systems across the globe and covers almost two-thirds of the world’s population. It highlights the broad spectrum and diversity of the world’s pension systems, and outlines shortcomings in even the top-ranking systems. The 2019 Index includes three new systems – Philippines, Thailand and Turkey.

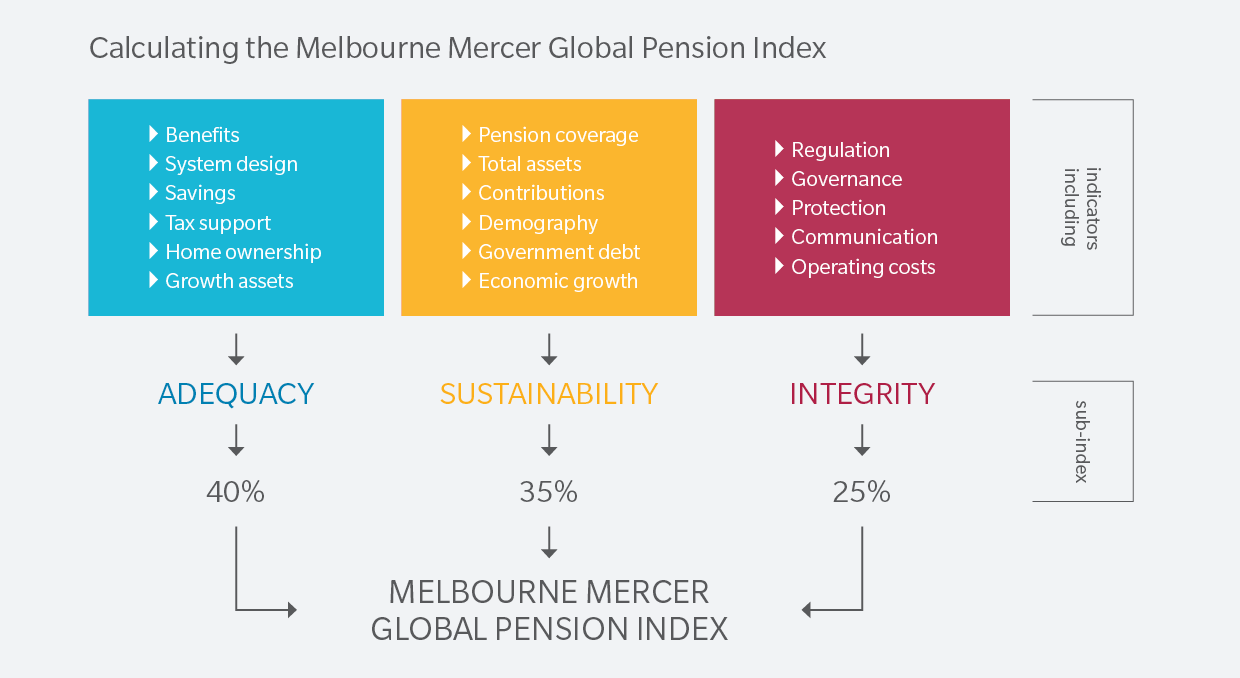

The MMGPI, supported by the Victorian Government of Australia, is a collaborative research project between the Monash Centre for Financial Studies (MCFS)—a research centre based within Monash Business School at Monash University in Melbourne—and professional services firm, Mercer. The Index uses the weighted average of the sub-indices of adequacy, sustainability and integrity to measure each retirement system against more than 40 indicators.

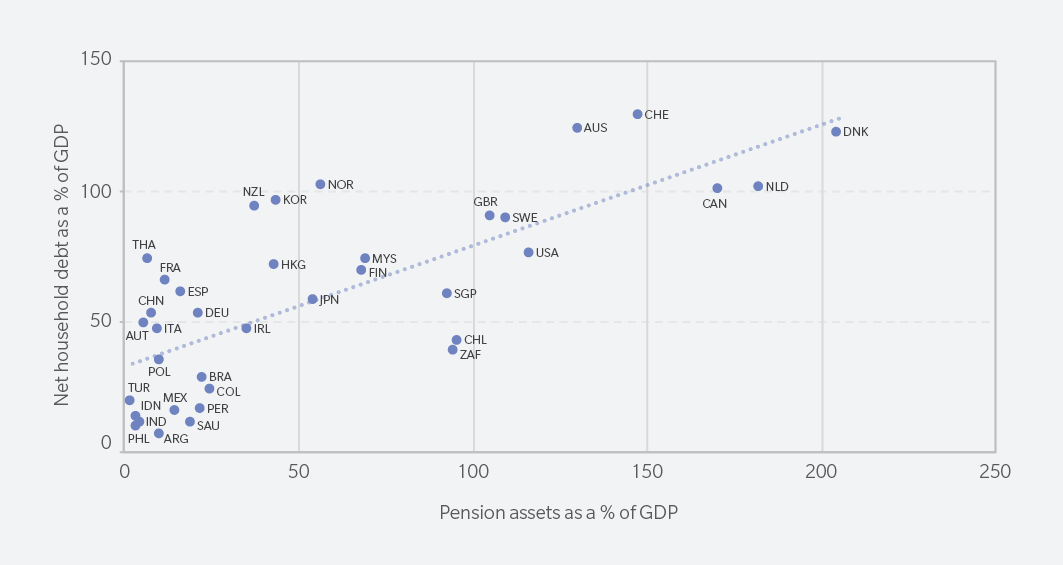

This year the report highlighted a “wealth effect”, with the tendency for household debt to increase with rising wealth, particularly in relation to pension assets.

“We have seen this before in terms of housing prices,” said Dr David Knox, a senior partner at Mercer and the study’s author. “As somebody’s house increases in value, they feel wealthier, and as a result they spend a little bit differently. What we see here is that people realise that they have superannuation assets which they may not have had before. These assets are available to them when they retire, and therefore seeing those assets as available to use to pay off debt after they retire.”

The MMGPI’s report suggests as pension assets increase, individuals feel wealthier and therefore may be inclined to borrow more.

“If I look at the Australian situation, we are seeing that the number of older people with mortgages is increasing,” Knox said. “In the Australian context, that may well be because houses became more expensive. But, in a recent paper, the number of 60-64-year olds with a mortgage has gone up by about 50 per cent over the last 10 years. So, while high house prices, are certainly a factor, it’s clear they are spending more under the thinking that they can use their super to pay off debt.”

The evidence demonstrates a strong relationship, with a correlation between net household debt as a percentage of GDP and pension assets as a percentage of GDP of almost 75 per cent. On a global basis, for every extra dollar a person has in pension assets, their net household debt rises by just under 50 cents, Knox added.

The strongly evidenced behaviour of households taking on additional net debt in relation to retirement assets suggests that sustainable pension systems should have a combination of lump sum payouts and income streams, Knox said.

“If people have debt when they retire, they can use some of the benefit to pay off the debt,” he said. “That would set them up for retirement, but they still have the regular income stream and a house to live in. Perhaps if they didn’t have the super coming, they wouldn’t be able to afford the mortgage. This behaviour also highlights the trust in the system over the long term.”

The relationship between pension assets and household debt’

There are universal demographic trends that are impacting retirement systems across the world, and Australia is no different.

“Certainly, people are healthier and some people are working longer,” Knox said. “We are seeing the labour force participation rate increasing gradually at older ages. It’s certainly true that some people in their 60s and 70s are in the workforce, but we have to be a little bit careful to also recognise that some people’s bodies wear out.”

Knox pointed to the fact that the preservation age in Australia is increasing to 60, with the Age Pension age rising to 67, a seven-year gap.

“Not all people are retiring at 65,” he said. “Some are worn out by 60, some are still working at 75. It’s a little more complicated than is often assumed. Part of that is the fact that some people think they are in good health in their early 50s, for example, and take on more debt under the assumption that they won’t need their pension until say 75, by which time they will have more in retirement savings.”

In Australia’s case, overall, the country scores 75.3, with a score of 70.3 for adequacy, 73.5 for sustainability and 85.7 for integrity.

Knox noted that Australia’s system, which has a mix of public pension and private savings through the superannuation guarantee, gives people and the government flexibility, which enhances sustainability.

“One of the big highlights here is that there are significant assets put aside for the future and that’s a good thing,” he said. Within the Australian context, the forthcoming review of retirement income gives the panel flexibility to think about how we structure future arrangements.

“In many developed economies, particularly in Europe, governments are going to be under pressure. What they do with the state pension will be difficult, whereas if you have assets set aside as we do in Australia, our aged pension costs are coming down as a proportion of GDP, giving future governments some flexibility.”

The report also uncovered the need to increase the coverage of retirement systems across populations.

“We need to increase the coverage of employees in the private pension system,” he said. “In Australia, it‘s compulsory, but you look at countries like the US and Canada, it’s strong, but only for half the population. How do you broaden that coverage?”

“Locally, we need to think about how coverage works for contractors or gig workers,” he said. “Gig workers are almost self-employed, but money is not being put aside for the future. How do we bring the self-employed into the private savings market? My view is that all workers should be putting some money aside for the future, whether they’re self-employed or an employee. How you get there is another question, but the workforce is changing and we need to recognise that everybody needs to defer some savings for retirement.”

The 2019 Index takes a new approach to calculate the net replacement rate – the level of retirement income provided to replace the previous level of employment earnings. While most previous Index reports have calculated a net replacement rate based on the median income earner, the current report uses a range of income levels based on the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development data to represent a broader group of retirees.

“Around the world, people are living longer. In all but two markets, life expectancy increased,” Knox said. “Interestingly, it’s the US and Mexico where life expectancy decreased. If people are living longer, governments need to think through what the state pension age is. That is a difficult political decision. We’ve seen in Australia it’s going from 65 to 67. A few budgets ago, the Government alluded to age 70 and it got knocked down very quickly. If life expectancies continue to increase, we may need to revisit this question.”